Film, Storytelling, and Conspiracies

An Interdisciplinary Academic Research Incubator at the University of Birmingham, UK

#PhilosophyMatters upcoming online event!

Monday 17 March 2025 2pm-3:30pm (14:00-15:30) GMT

Online - Zoom

Register for the event here.

More info here.

Join the first event, which is part of a new series of UoB #PhilosophyMatters webinars on the importance of Philosophy supported by The Royal Institute of Philosophy

What is the role of philosophy in tackling the presence of conspiracy theories in society? This webinar showcases the interdisciplinary nature of the philosophical work being done in this area, working alongside scholars in Film Studies, Theology, Psychology and Adaptation Studies.

The webinar is chaired by Lisa Bortolotti and will feature as panellists Alaina Schempp, U-Wen Low, and Kathleen-Murphy-Hollies. Lisa, Alaina, U-Wen and Kathleen are all members of an interdisciplinary project, ‘Film, Storytelling and Conspiracies’, and will talk about how a common focus on ‘storytelling’ is guiding collaborative work on conspiracy theorising.

About the incubator: Bringing together an interdisciplinary community of scholars

Film, Storytelling, and Conspiracies is an interdisciplinary academic research incubator that seeks to uncover the practice-related, regulatory, philosophical, religious, and socio-technical conundrums of re-telling conspiratorial stories, and creating space for new conspiratorial stories, that are raised (or resolved) by digital making.

Although digital technology may increase access to and engagement with arts, culture, and community, the democratization of digital making is not cost free. In our Incubator project we want to consider, in particular, the dangers posed when it comes to conspiratorial thinking in viewers of this media. In the broadest terms, and in collaboration with researchers in Film and Media Studies, Adaptation Studies, Theology and Religion, and Philosophy, we want to explore the idea that engagement in certain media influences what one takes to be possible. In particular, it is not mere film, but its artistry, that can facilitate conspiratorial ideation. There are two prongs to our overall approach.

The Stories we Re-Tell Ourselves and The Stories Made Possible

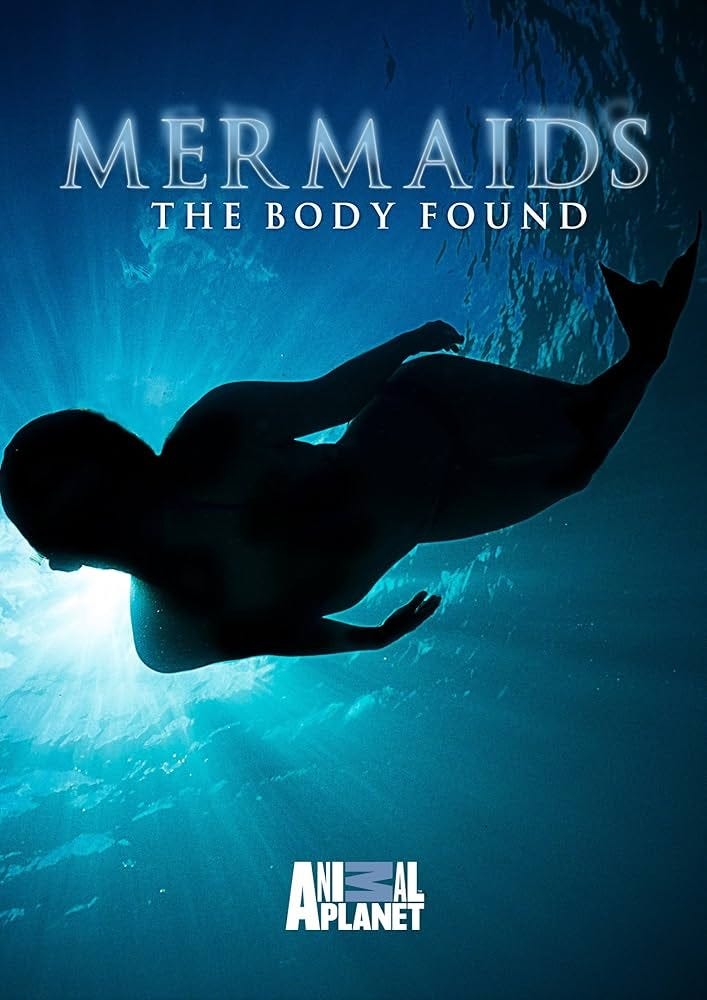

The first prong, The Stories we Re-Tell Ourselves, seeks to address the question of how audiovisual media and other paratexts (past and present) of conspiracy theories gain traction and, in some cases, challenge or replace previously accepted interpretations, transforming consensus interpretations of historical events (i.e. who killed JFK and why), scientific consensus (i.e. the theory of evolution), or facts about the world (i.e. the roundness of the earth). Conspiracy theories pre-date modern media; we will explore early conspiracies found in ancient texts, such as the theory of Jesus’ body being abducted, or theories concerning eschatology (the end of the world). Exploring these early conspiracies will provide us with helpful frameworks for establishing how and why conspiracies are developed and propagated amongst communities, and will show that conspiracies are not solely a modern phenomenon. Looking to the 21st century, modern media such as films supplement written texts as tools for propagating conspiracies. By dramatizing a convincingly realistic account of what could be, fictional films such as JFK (Oliver Stone, 1991) and Animal Planet’s documentary-style television film Mermaids: The Body Found (Sid Bennet, 2011) widen the possibility for what could be true. A film depicting what a conspiracy theory would look like were it actual, might lend that theory epistemic credibility in the minds of viewers. It is one thing hearing of a conspiracy, it is quite another to have the machinations of that conspiracy presented to you visually, and in an artistically compelling way. Equally, films could further a conspiracy, simply by omitting a visual representation of the consensus view. For example. the documentary Behind the Curve (Daniel J. Clark, 2018), which showcases clips from the 2017 International Flat Earth Conference, offers a neutral but sympathetic look at people who believe that the earth is flat, which potentially problematises its intended impact. We want to explore the role of conspiratorial narratives, as they are presented in film, in changing perceptions of the possibility and plausibility of particular conspiracy theories.

The second prong, The Stories Made Possible, is more indirect. We want to explore whether broadening the range of hypotheses one considers credible, conspiratorial narratives enter the space of plausibility. For example, digital tools have made possible highly realistic and compelling representations of space travel and disaster without, of course, any actor leaving Earth. This might reveal - to those with cognitive styles which tend towards being more suspicious, paranoid, and contrarian - that the moon landings may have been faked, or that recent images from NASA depicting a spherical Earth are manipulated. In a development of the ideas in our first prong about the role of films in making conspiracy theories plausible, in this second prong we consider how compelling films might be used as evidence for conspiracy theories, including popular religious films and conspiracies. A helpful example is the 2023 ‘documentary’ film The Sound of Freedom which has been linked to, and propagated, several conspiracy theories (e.g. QAnon) under the guise of telling a ‘true story’, in particular, as evidence that we have the tools available to make certain conspiracy theories possible. Taking our two prongs together, in our project we want to do three things:

Identify the psychological mechanisms that underlie the relationship between digital making and conspiratorial ideation.

Identify the social, political, religious, and philosophical issues arising out of the identification of such mechanisms.

Work towards a pre-emption toolkit for engaging in such media, by working with local schools and other stakeholders to understand the relationship between digital making and strange beliefs with growing social currency.

Although digital making may increase access to and engagement with arts, culture, and community, there are associated costs when we consider the possible spread of conspiracy theories. In the first place, when the production values and general artistry of a film depicting a conspiracy are of sufficient quality, might that conspiracy strike a viewer as more plausible than it otherwise would? And could hyper realistic computer-generated audiovisual images be taken as evidence that anything could be faked? Thus, widening the space of possibilities that one might consider?

Who we are

As a team, we are well-placed to deliver this project. Lisa Bortolotti, Kathleen Murphy-Hollies, and Ema Sullivan-Bissett have significant expertise in the philosophy and psychology of conspiracy theories, with growing publication records in this area as well as previous grant capture. In addition, Bortolotti and Murphy-Hollies have extensive experience in conducting public events at local and international levels discussing conspiracy theories, including public-facing workshops and museum curation. Other philosophers who have agreed to be involved (Chiara Brozzo, Nikk Effingham) also have interest and developing expertise in these areas. Alaina Schempp specialises in the analysis of cognitive and emotional effects of film and television. As an adaptation scholar, Christina Wilkins has a growing publication record in the retelling of stories. Other film, drama, and media scholars (James Walters, Rich Matthews, Sabrina Speranza Signorelli) have an interest in developing their expertise in this area. Candida Moss and U-Wen Low are biblical scholars with specific interest in 1st century CE culture pertaining to the production and performance of texts, as well as contemporary Christianity.

How to contact Us

The co-principal investigators of this University of Birmingham College of Arts and Law sponsored incubator are Dr Alaina Schempp (a.p.schempp@bham.ac.uk) and Dr Kathleen Murphy-Hollies (k.l.murphy-hollies@bham.ac.uk).